Author: Edgardo Civallero, former librarian and archivist at CDF

One goes over the spines of the documents that make up the collection of the CDF Library and comes across a small linguistic mixture. In addition to English and Spanish, the stronger languages, many others have nested among the old wooden shelves: from Mandarin, Japanese and Korean to Russian, Swedish and German, going through French, Italian and Dutch.

And even a couple of indigenous languages.

Due to the strong presence of migrant communities of the Otavaleño and Salasaca peoples in Galapagos, both of them coming from the Andean area of continental Ecuador, it is almost logical that in our collection we have a small ―unfortunately, still very small― handful of works that include translations into Quechua, Kichwa or Runasimi (literally, "the human language" or "the language of the people").

The book Siémbrame en tu jardín: jardines nativos para la conservación de Galápagos ("Plant me in your garden: Native gardens for the conservation of Galapagos") (2017) is an excellent example of such works. On its pages, which present files on island plants, the corresponding Runasimi translations are included. The title of the work, in that language, reads Kanpa sisapampapi tarpuway: Galapagos suyu kuskata kamankapak sisapampakuna.

We also have a book that is printed in Runasimi, which refers to Darwin's arrival in Galapagos: Charles Darwin Galapagos yawatipi kashkamanta: 15 kuski killamanta, 20 wayru killakama 1835 watapi (a sentence that, according to my rusty knowledge of Kichwa, would translate as "About Charles Darwin's stay in the Galapagos Islands: from September 15 to October 20, 1835").

Finally, we have a children's story, Sisa: descubriendo la diversidad cultural de Galápagos ("Sisa: discovering the cultural diversity of Galapagos") (2013), with a bilingual Castilian-Kichwa text.

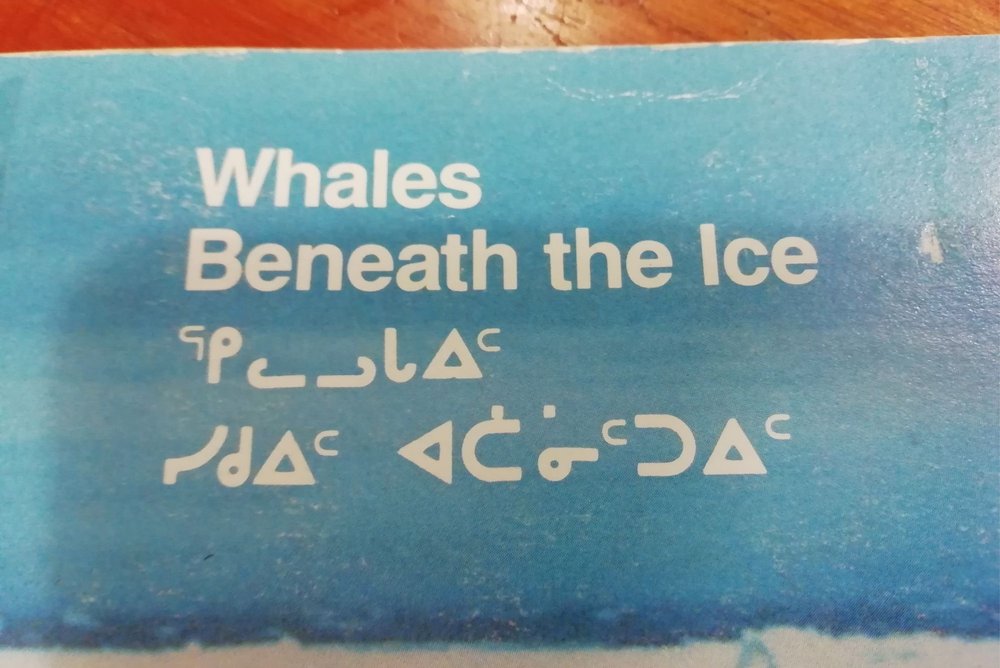

And that's it, I thought. What would be my surprise when I came across a WWF report entitled Whales beneath the ice (1986), the text of which is written in English… and Inuktikut!

The Inuktikut language is spoken by the Inuit ―one of the indigenous peoples popularly known as "Eskimos"― and has various forms of writing, depending on the group or "tribe" that uses it. The Inuit living in the Nunavuk and Nunavik regions of Quebec, Canada, use a system called qaniujaaqpait. It is a syllabary, that is, a code in which each sign represents a syllable (as in the case of Japanese hiragana).

The graphic form of each sign is very curious, and its history, even more. The system is the adaptation of a script developed by missionary James Evans around 1830 for the Cree and Ojibwe indigenous societies of Canada and the USA. Other evangelizers brought that idea to the far north of the Americas and there, in the solitudes of the Arctic, they used it to print the Gospels and to transmit Christian doctrines to the "Eskimos". The qaniujaaqpait consists of a dozen basic graphs to which the orientation is changed and annex symbols are added; in this way it is possible to represent the entire range of Inuktikut phonemes.

I found these letters one afternoon, as I finished sliding my finger down the spines of the documents that make up our bibliographic collection. I understood that, beyond the curiosity and amazement that these forms of writing produce, it is interesting that in our information repository we have such samples of the cultural diversity of our species. They remind us that on this small planet that we inhabit, knowledge is produced, circulated and reproduced in a multitude of media, codes and systems. And, at the same time, they allow us to contemplate our own wealth: the fantastic plurality of our identities, speeches and worldviews.

A plurality to value, care for and defend. Because it is equivalent to that other plurality, the biological one, that we protect in the CDF every time we fight to prevent the disappearance of a species. Because we know that, without these threads (big or small, it doesn't matter), the natural and cultural fabric of our world would end up unravelling.