Author: Edgardo Civallero

Academic texts on the history of the book say that during the Middle Ages, when Europe wrote on parchment and paper was still nothing more than an exotic resource in the hands of the Arabs, those thin sheets of leather were used and reused until the surface of the material refused to receive a single more stroke of ink. For parchment (at least the good quality one) was made from the skin of calves, usually neonates. And that was not a very common element in peasant societies for which a dead calf (and especially a newborn) was a real misfortune, a terrible loss, and who therefore cared for their animals better than their own children.

Therefore, in the monasteries where medieval codices were made, reproduced, translated, and transcribed, parchment was saved by continuously reusing it. Previous texts and drawings were scraped off, the surface was sanded (with shark skin, pieces of horsetail or sand glued on leather) and writing, drawing, and painting were done again. The problem is that the very nature of the inks of that time (powerful iron gall compounds, or products based on heavy, even toxic, minerals) made complete erasure, if not impossible, at least quite difficult. That didn't stop well-intended monastic scribes from swiping their quills over those surfaces over and over again. The end result is known today as a palimpsest (from Greek "scratched again"): text on text on text, in successive layers that reveal, with a little effort, the previous ones.

[The phenomenon also occurred with Egyptian papyri, Asia Minor scrolls, Mesoamerican amatl paper codices, and Indochinese bamboo manuscripts. The only ones that were saved from the palimpsestic problem, due to the very plastic nature of their materials, were the Mesopotamian clay tablets and the Greco-Roman wax plates].

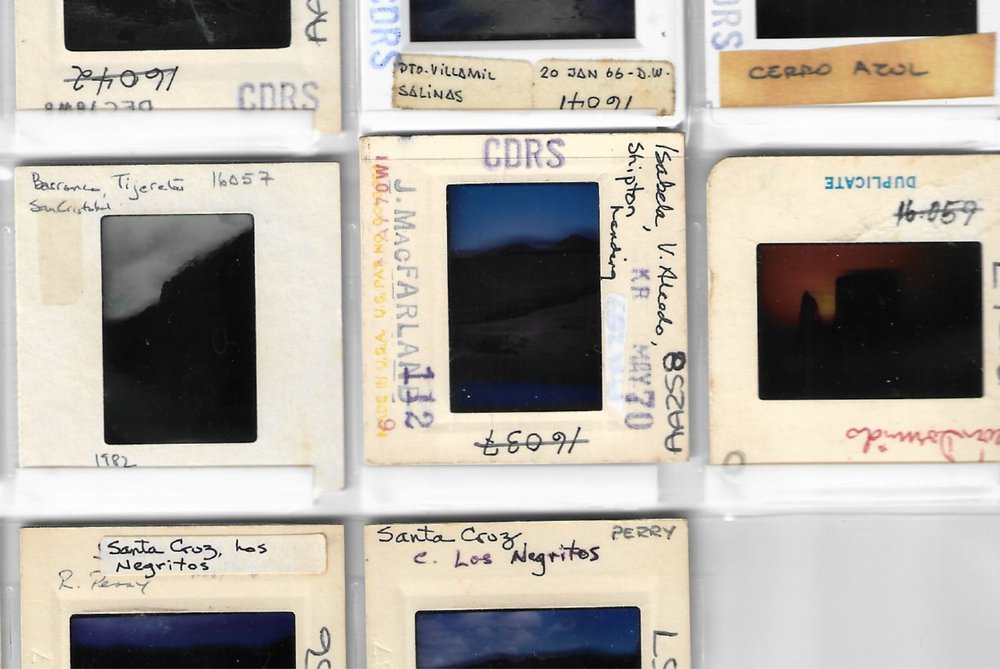

No: at the CDF Library, Archive & Museum we do not keep any of those valuable old documents. However, we do have materials that, with a little open-mindedness, can be considered palimpsests. I am referring to the frames (cardboard, plastic, metal, glass) of some of the more than 17,000 slides that we maintain in our audiovisual collection.

Some of the series that make up those collections are about 40 years old, and they were passed from hand to hand and from person in charge to person in charge throughout those four decades. The original author had placed some essential data in the frame of the slide (usually a location and a name), and his / her successors added elements. In most cases, they wrote alpha-numeric or numerical codes that allowed the identification of the object, but that, after some reorganization, were crossed out or partially covered with white ink (of the kind used to correct the mistakes of the old typewriters) and altered, sometimes more than once. Scientific names were also corrected, especially when the photographer was not a scientist and was not familiar with the spelling of Latin binomials.

Other times the description or the place was corrected, since many authors or curators wrote in Spanish despite not being native speakers of that language and, therefore, spelling errors were appalling. There are occasional fights over authorship, and in a couple of cases, an author who used to sign with a married surname deleted the last element of her name to return to her maiden designation.

It is needless to point out the amazing variety of colors, pen types and calligraphies; the abundance of stamps overlapping other stamps; the many dates that correct other dates… Some slide frames are a frightening mess in which it is very difficult to put some order. Which info is the earliest? Which one is reliable? It is necessary to review other sources to contrast every bit of information encoded around the sensitive photographic film.

After that, one can try to imagine the long process (a process of decades) that led to that framework exhibiting all those marks: battle scars that did not disappear and that will continue to tell their story as long as they manage to stay there.