1965-1970: days of discovery, institution building, start of tortoise rearing, tourist design and first park officials

Author: Tjitte de Vries

Very few students in biology after finishing their Masters have had their university professor and tutor calling in to his office saying, “UNESCO needs an ecologist for Galapagos and I think, Tjitte, that is something for you.”

That indeed was my first eye-opener for Galapagos. Bureaucracy started and information that I wanted did not come much beyond Beebe’s Galapagos, Worlds End. Passing through UNESCO’s Headquarters in Paris and meeting Prof. Jean Dorst, the then President of the Charles Darwin Foundation (CDF), who gave me the latest news he knew on the Charles Darwin Research Station. Boarding a plane to Quito, arriving with a telephone number of the UNESCO officer to announce my presence. A taxi arrived and a nice driver brought me to Hotel Embajador in times with few houses north of Avenida Colon.

No news was available for transport to Galapagos, “may be over a month or so”. That was the time in the 1960s. As far as science was concerned, I was advised by Don Cristobal Bonifáz, with a nice evening dinner at his home, to contact Prof. Gustavo Orcés, zoologist and museum director at the Escuela Politécnica Nacional, the botanist Dr. Acosta Solis, with an extensive library in the Calle Manabí, and Dr. Plutarco Naranjo, then director of Life Laboratories in the Avenida de la Prensa.

These three men of fame briefed me on science and conservation in Ecuador. When finally, there were words on transport to Galapagos I boarded “the early” train (6:00 am) from Quito to Guayaquil (Duran), a 12-hour journey with magnificent landscapes.

In Guayaquil after a week the Cristobal Carrier left for a five-day journey and arriving at Santa Cruz I was welcomed by Edgar Pots with the amazing words “En meneer de Vries heeft u een goede reis gehad?”, his soft ‘g’ indicated his Flemish origin. I straight away felt like home on the island of Santa Cruz, living the first years in the Summer House of Mrs. Horneman, near the Station’s beach. This nice little cottage was later broken down and changed in a rather ugly building named FitzRoy Palace by Ole Hamann.

The mid ’60s was still a time for exploration, getting information on the population size of the tortoises, flamingo, penguin, flightless cormorant, and albatross census. Eggs of the Pinzon tortoise were collected and placed in incubators at the Station and with Roger Perry, Miguel Castro, and Camilo Calapucha we were looking for the last tortoises in Española to bring them to the station in breeding enclosures.

The first permanent vegetation plots where established, later extended by Ole Hamann and Henning Adsersen. Mike and Rosalie Harris were there to study seabirds, and we formed a nice station family with David and Debby Clarke, Henk and Nita van der Werff, Jerry and Pat Wellington, Guy Coppois, and others, having the 10 o’clock coffee in the Comedor at the seaside and lunch around 12 o’clock with Jhonson saying “eat men eat”. In the afternoon at 17:00 one hour of entertainment with a game of volleyball, on the sandy site in front of where later the new house of the director was built.

When I now read the scientific papers on the results of seabirds, introduced rats, vegetation, oceanography and land snails, the moments of joy and friendship come back.

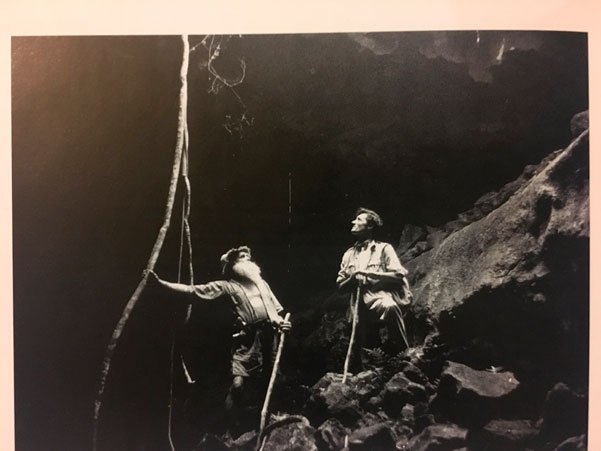

Also, it was a time to hear and learn the experiences of the early settlers, the Rambech’s, Kasdalen’s, Angermayer’s, and Carlos Kübler exploring lava caves. The Beagle II were to arrive in these days and was in the beginning of great help to visit the Islands but became later a headache in maintenance.

That the station could be run with Roger Perry at the helm, Rolf Sievers after Edgar Pots as manager and Roberto Schiess, Miguel Gallardo, Carlos Robalino and Abraham Rosero as carpenter is really amazing. These were amazing times if you now see the place of the workshop building changed in an exhibition hall.

I spent many evenings with Roger collecting moths in front of the door of the laboratory building, many of which were determined by Alan Hayes at the British Museum of History, so were Roger and myself united as a Siamese twin: Utetheisa perryvriesi.

In his “island days” Roger Perry gives an idea of visitors to the station, “It was the visiting scientists, individualist all of them in their way, who provided us with company, amusement, enlightenment, and to a considerable extent, scientific justification for the existence of the station.” One scientist who wanted to cross the island of Santa Cruz from the southern beaches of Baltra over the top to Bellavista, (without a scientific purpose), did not have much of my support. I recently had crossed with Chappy from Whale Bay to Santa Rosa so I knew the many difficulties to find the way. Luckily, she never came further than the beach looking on her knees to search for her compass.

We had a lively time in those early years but not without problems: fishermen from San Cristobal protested when the Station started goat hunting on Española, border disputes with colonists in the highlands where Park limits were set, tourist development with a Grimwood-Snow Report and visits of Eduardo Proaño of Metropolitan Touring and Lindblad Travel coming for the first time with the vessel SS Navariño .

Juan Black and Jose Villa came as the first park employees, paid the first year by Lindblad, at the same time more and more became known about the flora and fauna, and the tortoise program was successful with hatching tortoises, and preparations were made to try to get rid of the introduced animals and plants. More details of problems and endeavors are available in the early numbers of "Noticias de Galapagos", in the more than 20 Scientific and Conservation Reports written by Roger Perry on an old Olivetti as well as in the highly interesting reading in his “Island Days”.