A long-dreamed opportunity for any biologist, I finally found my way to the Galápagos Islands last March. On the second week of my new position at the research station of the Charles Darwin Foundation, we embarked on a week-long field trip to the north of the archipelago: the islands of Darwin and Wolf, the sharkiest place in the world. Welcome to Galapagos to me!

Why Galapagos?

The Galapagos Marine Reserve was declared a protected area in 1998, giving this archipelago the opportunity to stay almost as pristine as it was before human settlement. Although finding balance is challenging, the community here understands the importance of protecting the islands’ natural resources as tourism is the main economic source here. This protected archipelago is an example of a productive relationship between human and nature. There is hope.

Sharks are heavily fished worldwide as a source of protein and also for Chinese soup, which has led many species of sharks (and their cousins, the rays: next blog) to decline during recent decades. Largely due to SCUBA diving, sharks have become a tourism attraction in many localities worldwide, such as Galapagos. It is now recognized that sharks are worth more alive than dead and thanks to the efforts of many scientists, conservationists and the community, sharks are now protected in Galapagos waters. Because of this, the northern islands of Darwin and Wolf were recently declared a sanctuary by the Ecuadorian government. This sanctuary was created to protect a key ecosystem that supports the largest biomass of sharks found globally so far, says the study done by scientists at Charles Darwin Foundation. It will hopefully ensure that the declining populations of sharks have a refuge to recover from the overfishing happening elsewhere.

The sharks team from the Charles Darwin Foundation, now led by Dr. Pelayo Salinas, has been monitoring sharks in Galapagos for a few years with the aim of understanding the role of this archipelago as a key habitat in the life cycles of sharks.

“These islands are a key ecosystem likely connecting populations of migratory sharks across the islands and mainland of the Eastern Tropical Pacific, and this information is vital for understanding the role of the Galápagos Marine Reserve in protecting threatened shark populations”

says Dr. Salinas-de-León.

So, twice a year the team embarks on a journey to the amazing islands of Darwin and Wolf located to the north of the Galapagos archipelago and kind of in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. The aim of these field trips is to continue with the monitoring of sharks and large pelagic fish, and eventually assess the impact of the new sanctuary on sharks’ populations.

The team I joined during this trip was formed by six other scientists with different backgrounds, which made the trip even more interesting.

Two principal scientists at the Charles Darwin Station, Dr Patricia Marti Puig, expert on corals and deep water invertebrates, and Dr José Marin Jarrín, expert on fisheries and Science Coordinator, joined the expedition. Also on the trip were field work coordinator and marine scientist Salomé Buglass and staff from the Galapagos National Park Directorate: Head of the Marine Biological Resources Program Harry Reyes and an external collaborator from the University of British Columbia, an expert on fisheries and climate change modeling, Dr Tyler Eddy. This mix of scientists was a great introduction for me into the Galapagos and the awesome work done by the Charles Darwin Foundation.

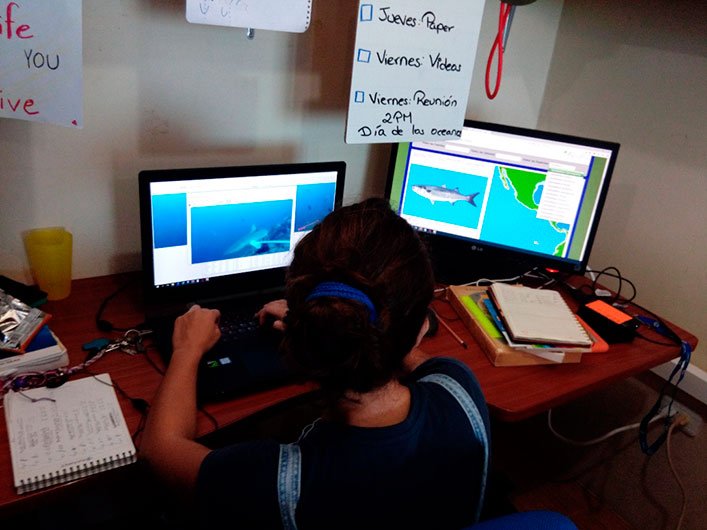

How do we monitor sharks? We take videos!

Baited Remote Underwater Videos (BRUVs) and Diving Operated Videos (DOVs) are two tools used to monitor marine life using underwater videos that are later analyzed in the lab. Basically, a BRUV is a camera mounted on a metal frame with a PVC tube holding bait in front of the camera, the frame is attached to a rope and buoys so that it can be deployed in the water for a set time, and then retrieved.

A DOV is a camera mounted on a smaller metal frame with small buoys and held by a SCUBA diver during an underwater transect. They are both ways to do underwater visual surveys, allowing the scientist to “revisit” the site as many times as needed through a video to get a more accurate identification of fish and other data.

During the trips to Darwin and Wolf, we used “stereo-BRUVs” and “stereo-DOVs”, which means that the frames each have two cameras instead of a single camera.

Having two cameras allows scientists to take measurements of fish and other wildlife seen in the video using software designed to do this. Measurements are then used to calculate biomass–which in this case would be the total mass of sharks per square meter.

Cruising aboard Queen Mabel, it took us about a day to slowly get to our destination — and a about another day to get back — and during five days we deployed BRUVs in eight key sites around each island, leaving them in the water for a couple of hours to film. We also did seven transects SCUBA-diving with DOVs at each island. The team is currently analyzing about 24 hours of videos taken by the BRUVs and about five hours taken by DOVs!

We expect to have results of a few years’ data from BRUVs and DOVs next year. This will be used to understand the use of Darwin and Wolf islands by sharks as key habitat, and to address other important questions like the effects of changes in temperature (climate change) on sharks.

But besides the scientific and sharky part of this trip...

“This place never stops surprising me with all the wildlife I see surrounding my boat every time I visit” said Vico, the captain of the Queen Mabel during the trip. Indeed, we got to see a lot of marine life on and around the islands: sea lions playing with the unaware divers in front of me during transects; many (so many!) birds nesting on the cliffs; a massive pod of dolphins that surrounded us and played with the smaller boat we were on; fins of orcas and sun fish breaking the sea surface.

These were my first dives in Galapagos and what a trip it was diving in Darwin and Wolf! It is amazing indeed to be able to see nature like this, untouched and yet protected. It makes you want to know more and understand these isolated ecosystems. It gives us hope that we can have an impact through our work as scientists. It makes me want to dive again there! Soon.

The Charles Darwin Foundation depends entirely on the generosity of our supporters. Please donate today to support our work.