When we talk about Galapagos we always think of Darwin, giant tortoises and finches. But few outside Galapagos know about the Scalesia plants, commonly known as Darwin’s giant daisies.

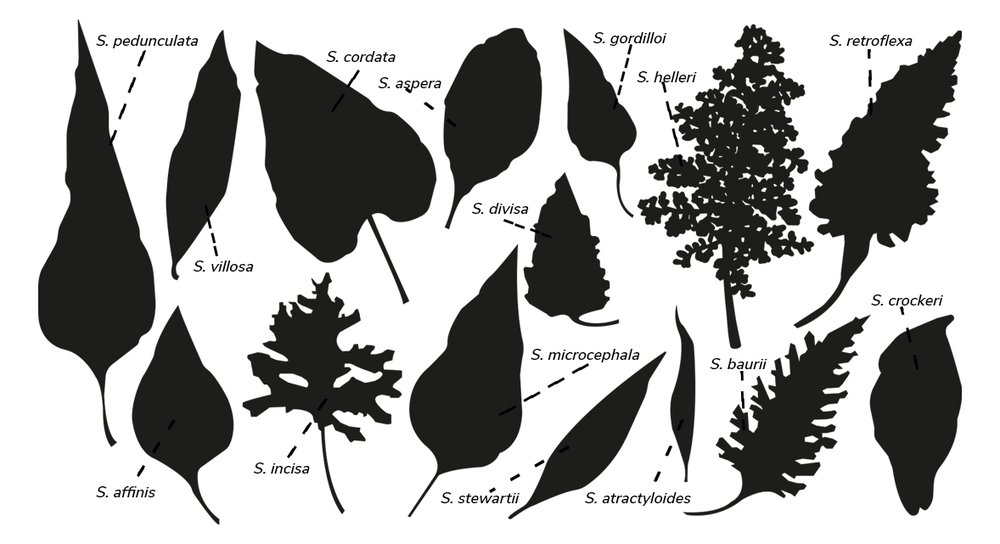

Scalesia is a genus of several plant species endemic to Galapagos. They exist nowhere else in the world. Like the shells of tortoises or the beaks of finches, these species have very different leaf shapes, depending on the island and climatic zone they inhabit. Evolution at its finest. There are 15 Scalesia species in the Enchanted Islands. Most of these are shrubs; only 3 are trees, one of which has heart-shaped leaves: Scalesia cordata. This species only exists in the south of Isabela Island.

I first heard about Scalesia cordata when I arrived in Galapagos in mid-2021 as a scientist at the Charles Darwin Foundation (CDF). Heinke Jäger, CDF researcher, told me that, in 2002, Patricia Jaramillo (another CDF researcher) and park rangers from the Galapagos National Park Directorate (GNPD) counted about 1700 trees at various locations on Isabela. Unfortunately, in 2019, Anna Walentowitz, a German graduate student, found less than 1% of the trees at the same sites. So, in August 2021, I had the opportunity to join a field trip to Isabela, to find where these trees were, see how many there were left, collect seeds and start the project: "Saving Scalesia cordata from extinction".

Searching for Scalesia cordata

The first day we went to Cerro Grande, which is located east of the agricultural zone on Isabela. As we reached the border with the Galapagos National Park (GNP) area, we could see guavas, cedrelas and other invasive plants. We walked 400 m into the protected area and there, inside a fence built by park rangers, I saw the Scalesia cordata trees for the first time. The few trees left were separated from one another and there were no juvenile saplings in the area to indicate regeneration in previous years. This situation worried me.

The second day we went to the rim of the Sierra Negra volcano. During the long hike, it was sometimes difficult to see where we were stepping, because a fern had invaded the whole area impeding our passage. Upon arrival, we observed no more than 15 Scalesia cordata trees, scattered across the landscape. But again, no seedlings or saplings.

On the third day, we went to Caleta Iguana. When we got off the boat and went up to the Scalesia area, the trail was full of "Siam weed" (Chromolaena odorata), considered one of the most invasive plant species in the world. In the area where Scalesia had formerly been recorded, we only found one juvenile among approximately 30 trees.

One question remained in the air... why is there no regeneration of this species? The reason is still unknown, but what we do know is that, if the situation continues, the day these trees die, this Scalesia species will be gone forever.

Hope ahead

Today, however, we believe that not everything is lost. CDF and GNPD have joined efforts to rescue the Scalesia cordata. We have collected thousands of seeds from ten different locations within the GNP and the agricultural zone, where some Scalesia trees can still be found. The GNPD greenhouse on Isabela now cultivates this species and we have already planted 75 saplings at four sites. Currently, there are more than 1000 healthy and beautiful seedlings, waiting their turn to join the Scalesia populations.

Meanwhile, invasive plant control is being carried out at six Scalesia cordata sites within the GNP. This control has allowed us to see Scalesia seedlings for the first time in several years. Our last expedition in November 2022 revealed that we already have natural regeneration with more than 250 seedlings at four of the original Scalesia sites. In addition, Pedro Gómez and Ernesto Bustamante, our Isabela technician and community liaison on the island, respectively, continue to raise awareness of Scalesia cordata among local producers, students and the people of Isabela. We are hopeful: the community of Isabela, CDF and the GNPD are motivated to save the Scalesia cordata from the brink of extinction. After all, tortoises and finches also depend on this habitat, so it is critical that we preserve it.