The Mystery of the Santa Fe Tortoise

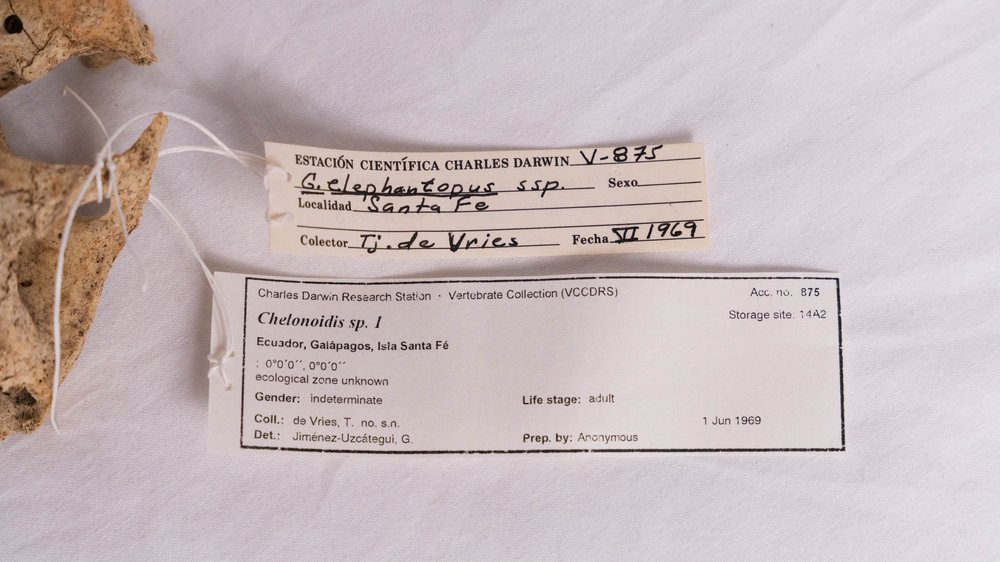

In 1969, the rains were relentless. For weeks, water poured without pause over the archipelago, softening the soil, carving gullies into the slopes, and washing away the gravel of Santa Fe Island. In the central part of the island, erosion etched deep channels. During those days, while returning from his rounds observing hawks, Tjitte de Vries, the first resident scientist hired by the Charles Darwin Research Station and now a member of the CDF General Assembly, came across something unusual.

“I was walking along my usual path, watching the wet ground carefully, when amid the gravel and rubble I spotted a white shape. I bent down. It was a skull: small, light, perfectly preserved of a tortoise.”

Carefully, he placed the skull in his backpack and returned to the Charles Darwin Research Station, where, together with the director at the time, Roger Perry, they were fascinated by the possibility that this skull might belong to the extinct giant tortoise species from Santa Fe.

There is solid evidence that an endemic species of giant tortoise once inhabited Santa Fe Island. Remains from 14 individuals were found during the California Academy of Sciences’ 1905–1906 expedition, all fragments of shells and other parts of the skeleton, but never a skull. DNA analyses published in 2011 confirmed that they belonged to a species different from those of other islands, but the species was never described. Additionally, at least two whaling ship records mention removing tortoises from Santa Fe. It is believed that the species became extinct toward the end of the 19th century, as whalers captured live tortoises to use as food during their long voyages when electricity did not yet exist.

The skull found on that rainy day is now kept by Miguel Pinto, coordinator of the CDF Natural History Collections, in Santa Cruz Island.

“This skull is important because it could serve as the basis for the description of the Santa Fe species, but first it must undergo a test to determine whether the specimen predates the mid-20th century. This test has to do with nuclear bombs,” explains Miguel.

Since the 1940s, humankind has used nuclear energy. The bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, along with later tests, released radioisotopes that remained suspended in the atmosphere and became incorporated into living organisms.

“Since the atomic bombs, all living beings carry traces of those radioactive isotopes in their bodies,” explains Miguel Pinto. “If the skull does not contain these traces, we could be certain that it belongs to the original Santa Fe species.”

A sample of the skull will soon travel to the United States for analysis. If its antiquity is confirmed, Tjitte de Vries’s discovery will represent the most complete specimen of the extinct Santa Fe giant tortoise and could provide crucial information for its taxonomic description.

Morphology of the Santa Fe Tortoise

Santa Fe Island is one of the central islands of the Galapagos Archipelago and, geologically, one of the oldest, with rock formations dating back to around 3 million years ago. Its landscape is characterized by a turquoise bay, a large sea lion colony, and vast forests of giant Opuntia cactus. In the past, it was known as Barrington Island. The island is mostly flat, and its geography and vegetation offer clues about the probable morphology of its extinct tortoise.

“The tortoises from Floreana, Pinta, and Santa Fe had saddle-shaped shells, a characteristic that allowed them to stretch their necks upward to feed on higher vegetation,” explains Courtney Pike, researcher from the Giant Tortoise Movement Ecology Program.

This shell shape reflects an adaptation to the arid, open environment of Santa Fe, where vegetation grows taller. The morphology of these tortoises reveals their close relationship with the landscape.

Isotope testing is now underway. Soon, the results will reveal whether this skull truly belonged to the legendary Santa Fe giant tortoise, lost for decades. If confirmed, it would not only rewrite a chapter of Galápagos history but also offer new clues about the evolution of these iconic reptiles.