Galapagos’ Tiny Guardians: Using Nature to Bring Back Nature

The Galapagos Islands are a world-renowned treasure and a true living laboratory of evolution. However, this fragile paradise faces a constant threat: invasive species. When a species arrives in a new place without its natural predators or parasites, it can spread uncontrollably, causing severe harm to endemic species and the ecosystems they inhabit. This threat highlights the urgent need for innovative and carefully designed solutions to protect the Islands’ unique biodiversity.

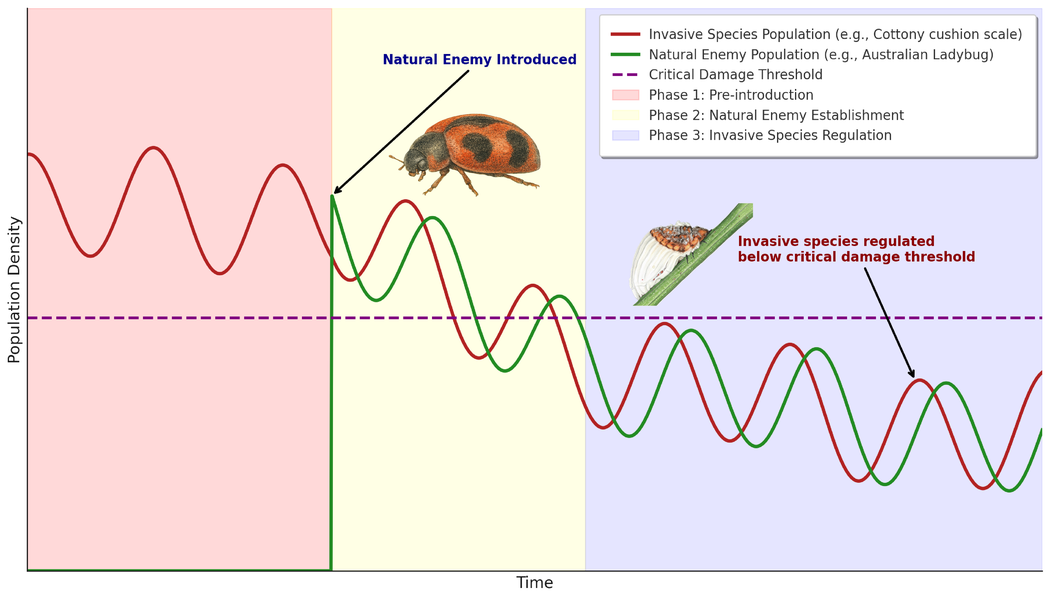

One of the most effective and delicate tools in conservation is biological control, which involves introducing natural enemies to regulate invasive species populations and restore ecological balance. The core idea of classical biological control is simple but powerful: a natural enemy that is specialist on the target species and that has been proven not to harm other species, is carefully introduced. These enemies, which can be predators, parasites, or pathogens, help reestablish the lost ecological balance by keeping invasive populations under control.

This method is especially valuable in Galapagos because it can be self-sustaining over vast and hard-to-reach areas, offering an ecologically friendly solution to conserve these sensitive ecosystems. To understand its effectiveness, we can look at one of the most emblematic success stories of conservation in the Islands.

A Famous Victory: The Ladybug That Saved the Scalesias and the Mangroves

A well-known success story in Galapagos is the biological control program using the Australian ladybug (Novius cardinalis), also called the vedalia beetle. Its target was the cottony cushion scale (Icerya purchasi), an invasive insect native to Australia that was devastating native and endemic plants in Galapagos, including the emblematic Scalesia and Darwiniothamnus species, endemic to the Islands, and several native mangrove species.

After years of careful research ensuring it posed no risk to native species, the Australian ladybug was introduced. This marked the first time that biological control had been used in Galapagos and it was a resounding success. The ladybug effectively reduced the invasive insect population.

The dynamics between the ladybug and the cottony cushion scale showcase how classical biological control works: when the cottony cushion scale is abundant, ladybug populations increase, reducing the invasive insect (Fig 1). As their food decreases, the ladybug populations also decline, allowing the scale to recover slightly. This natural cycle creates a long-term balance, keeping the invasive species below the critical damage threshold. Thanks to this strategy, the ladybug has become the silent hero of many plants in Galapagos.

The Next Challenge: Tackling the Avian Vampire Fly

While the biological program using the Australian ladybug was a success, new threats require equally innovative solutions. One of the most urgent for Galapagos’ small land birds is the avian vampire fly (Philornis downsi). Originally from mainland Ecuador and other South American countries, this fly arrived in the Islands without its natural enemies. It lays its eggs in the nests of about 79% of Galapagos’ small land bird species, including many of Darwin’s finches and the emblematic Little Vermilion Flycatcher (Pyrocephalus nanus). The larvae feed on the blood of nestlings, often causing their death.

Controlling this fly is highly complex: it is found throughout most of the archipelago, and much of its life cycle occurs high in the forest canopy. For this reason, biological control has emerged as the most promising long-term solution. Since 2013, scientists have been studying natural enemies of the avian vampire fly in mainland Ecuador, focusing on areas with climates similar to Galapagos, and have identified two species that specifically target Philornis downsi.

This meticulous research led by the University of Minnesota and the Charles Darwin Foundation, in collaboration with the Galapagos National Park Directorate and other institutions ensures that any potential biological control agent under evaluation is safe for the Galapagos ecosystem. Scientists are conducting detailed tests to confirm that these natural enemies are highly specialized and will target only the avian vampire fly, thus protecting the integrity of the ecosystem.

Hope for the Future

The Philornis downsi project represents the most advanced biological control program currently under investigation in Galapagos, and its findings could help advance programs for other priority invasive species, such as the tropical fire ant (Solenopsis geminata) and the blackberry (Rubus niveus).

Biological control is not a quick fix; it is a long-term commitment to rigorous science and safety. Its goal is not to eradicate invasive species completely but to achieve a sustainable and lasting balance. The success of the Australian ladybug demonstrates what is possible, and the ongoing research on the avian vampire fly gives us hope that Galapagos’ small land birds may one day have an ally to help them beat their deadliest threat, the avian vampire fly.

Learn more about this project and discover how you can be part of the change.